Wow!

Public Library Exploration #1: On Navigating Difficult Conversations and Noticing Native American Spirituality (featuring constructive critiques for the Boy Scouts' Order of the Arrow)

[As of 6.5.25 at 7:03 PM, check out this brand new song from yours truly!]

[I, Weston, wrote the following around 5.13.25]

Wow!

In tune with the etymology of that word (‘wow’), I am now writing from a psychological headspace of being “overwhelm[ed] with delight [and] amazement”!

This past February (three months ago), I was able to write and publish ‘Magic Through Rhetoric’ as well as ‘Prisons Need Prohibition’. But then I found that I needed to take a break from Substack posting. I’m nearing the end of my coursework for the ‘Classical Culture’ track within Villanova University’s online Classical Studies M.A. degree, and I had needed to focus more exclusively on writing final essays for Prof. Sarah Wahlberg’s Greek Tragedy class, Prof. Andrew Scott’s This Is Sparta class, and Prof. Collin Hilton’s Cicero class. At this point, I just have to complete a summer class and a cumulative exam in order for me to finally earn my degree— and then I need to figure out how to market myself so that I can start earning money again(!).

Now that I’ve completed those final essays for Spring 2025, I have some room to breathe and I have been on a creative streak lately— e.g. I have been trying out Instagram Live piano performances :)

[I, Weston, have been working on the following between 5.13.25 and 6.3.25]

In what follows, I would like to share some interesting tidbits from 8 books— starting with the newest book and moving toward the oldest book.

In this post, I will be addressing the following two texts. Recently, I visited the beautiful Bella Vista Public Library and picked up a copy of “Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most” (2023) by Drs. Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen. Additionally, I visited the epic Fayetteville Public Library and picked up a copy of L.M. Arroyo’s ‘Native American Spiritualism: An Exploration of Indigenous Beliefs and Cultures’ (2023).

In the next post within this series, I would like to address the following 6 books that I picked up from the excellent Bentonville Public Library: firstly, Kerry Connelly’s ‘Good White Racist: Confronting Your Role in Racial Injustice’ (2020); secondly, Duane R. Bidwell’s ‘When One Religion Isn’t Enough: The Lives of Spiritually Fluid People’ (2018); thirdly, Shashi Tharoor’s ‘Why I Am A Hindu’ (2018); fourthly, Ralph T.H. Griffith’s translation of ‘The Vedas: From The Ancient Sanskrit’ (2010); fifthly, Eknath Easwaran’s translation of ‘The Upanishads’ (2007); and sixthly, David Kinnaman and Gabe Lyons’ ‘Unchristian: What A New Generation Really Thinks About Christianity…And Why It Matters’ (2007).

While I will not have time (or space) to provide fully-baked book reviews, I am very much looking forward to mining for gold nuggets of wisdom within these texts.

As the Doctor would say: “Allons-y!”

Book 1/8: “Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most” (2023) by Drs. Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen.

In a book like this, I suppose I could have expected to come across wonderfully challenging sentiments like this: “we are all human beings who want to love and be loved, see and be seen” (2nd Edition Preface, Pg. xvii). However, I was for sure delightfully surprised to read that a “dance instructor uses [this book] to teach Argentinean tango” (2nd Edition Preface, Pg. xvi)— wow!

That this book on communication skills has been used to teach dance classes tangentially reminds me of this study which claims that several 16th century musicians—including J.S. Bach—utilized speech-structures from Roman speakers like Cicero and Quintilian (consider Pgs. 93 and 95 within: Kirkendale, Ursula. “The Source for Bach’s ‘Musical Offering’: The ‘Institutio Oratoria’ of Quintilian.” Journal of the American Musicological Society, vol. 33, no. 1, 1980, pp. 88–141. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/831204. Accessed 12 Mar. 2025.). Although I don’t have enough time or space to launch into an exhaustive exploration of intersections between dance, music, and speech, I find myself agreeing with this notion that conversation partners and dance partners have much in common.

If participating in a dance might involve ‘me’ needing to be aware of rhythms being performed by musicians, an awareness of ‘my’ movements, an awareness of ‘my’ partner’s movements, and an awareness of the movements of other dance partners around my partner and I, so we might likewise imagine that participating in a conversation requires much awareness of space and time. In this book, the authors suggest that “each difficult conversation is really 3 conversations” (Ch. 1, Pg. 15)— there’s the conversation surrounding ‘What Happened?’, there’s the conversation surrounding ‘Feelings’, and there’s also the conversation surrounding ‘Identity’. Essentially, the authors suggest that—although it is painfully easy for me/us to cast blame upon our conversation partners, to make assumptions about the intentions of conversation partners, and to think that I/we are on the side of ‘the truth’—we would benefit by doing the hard work of acknowledging that we have differing perceptions or feelings about how to interpret what is valuable/important. According to the authors: “Engaging in a difficult conversation without talking about feelings is like staging an opera without the music. You’ll get the plot but miss the point.” (Ch. 1, Pg. 22) Where we might feel compelled to participate in ‘A Battle of Messages’, the authors propose that we need to do the internal work to prepare ourselves for ‘A Learning Conversation’ (Ch. 1, Pg. 26). Dr. James Vargiu once concisely suggested that “there are in each of us a diversity of these semi-autonomous subpersonalities striving to express themselves.” (within ‘Howdy’, I referenced Vargiu’s article on ‘Subpersonalities’ [1974])— and, if this is so, I suppose that our sense of identity is perhaps far harder to figure out than we might wish. Much as Dr. Vargiu suggested that we may not be aware of all voices/characters within us, and much as Prof. Richard Whately once suggested that “in any course of Argument, one Premiss is usually suppressed” (within ‘The Cutting Edge Notes’, I referenced Whately’s ‘Elements of Logic’ [1827], Ch. 3, Pg. 137), so also these authors suggest that we must try to pay special attention to what is not said in any particular conversation— for instance, ‘Jack’ thought and felt things which he did not explicitly share in his conversation with ‘Michael’ (Ch. 1, Pg. 13).

If it feels true that “Delivering a difficult message is like throwing a hand grenade.” (Introduction, Pg. 3), the authors—refreshingly—suggest that “We need advice that is more powerful than ‘Be diplomatic’ or ‘Try to stay positive.’ The problems run deeper than that; so must the answers.” (Introduction, Pg. 4) In the process of concluding this book, the authors are forthright enough to provide this sobering sentiment: “All you can do is take a hard look at yourself, be open to seeing things differently, change your own contribution, and be honest about what matters to you. You can extend an invitation to join you in working to improve things. It’s up to them whether to RSVP.” (A Final Thought, Pg. 359) But I think that the authors also did well to suggest that “for every case that is truly hopeless, there are a thousand that appear hopeless but are not” (Introduction, Pg. 6). Moreover, I love this encouraging note: “For if we are fragile, we are also remarkably resilient.” (Introduction, Pg. 7)

A Couple Lingering Questions:

How can we become more self-aware?

How can we become better conversationalists?

Book 2/8: L.M. Arroyo’s ‘Native American Spiritualism: An Exploration of Indigenous Beliefs and Cultures’ (2023)

Being a 1/32nd citizen of the Muscogee Creek Nation, I am excited to explore this book further!

Let’s start by looking toward the end— what the Greeks might have labeled as the τέλος (a transliteration = telos). In the Conclusion (Pgs. 158-159), Arroyo seems to paint a picture wherein humans at least manifest as Native Americans and as non-Native Americans. Her concluding paragraph proceeds thusly: “A willingness to self-interrogate, even when there are hard truths to uncover, is a surefire way to grow. The moment non-Natives are able to humble themselves—realizing that their knowledge has been limited as a result of centuries of colonization and oppression—the doors to true understanding and brotherhood are thrown wide open.” (Arroyo 159) Where that penultimate sentence immediately reminds me about the New Testament counsel to “examine yourselves, to see whether you are in the faith” (2nd Corinthians 13:5), the former portion of the ultimate sentence reminds me of the New Testament advice to “humble yourselves before the Lord, and he will exalt you.” (James 4:10).

While mentioning such New Testament texts sparks fascinating questions within me about who authored these texts, how they came to be adopted into the New Testament canon, how they have been translated over time, and whether the sentiments which they express are true, I mention such New Testament texts to suggest that the idea of admiring humble self-interrogation is perennial and cross-cultural. In other words: I think that Arroyo’s moral exhortation is (1) applicable to exploring how non-Native Americans can and should treat Native Americans and is (2) also applicable to exploring how all humans can and should relate to each other. Above the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, it has been said that this exhortation was written: γνῶθι σεαυτόν (translation: “Know yourself!”). Like the previous book about communication (by Drs. Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen), then, Arroyo seems to hope that this book will help us become better neighbors in life through becoming more self-aware. At the end of the day, I too hope I’m becoming the kind of person who asks: how have I been doing in terms of (e.g.) introspection?

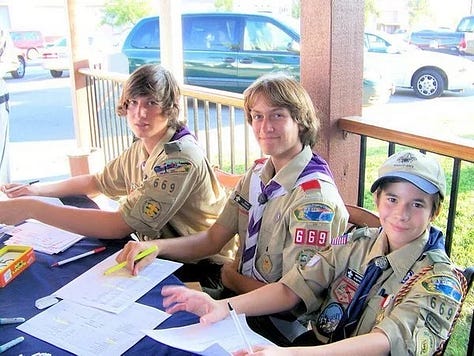

In the beginning part of the Introduction, I appreciated that Arroyo suggested that Native Americans generally are more concerned with “living and breathing” their spirituality (than being concerned about "believing” their spirituality) such that “It melts into every aspect of life—there is no separation between art, work, love, nature, family, and religion—they are all one.” (Arroyo 8) In the latter part of the Introduction, I appreciated that Arroyo proposed a distinction between polite ‘appreciation’ of Native Americans and impolite ‘appropriation’ of Native American customs. Arroyo provides two examples of impolite ‘appropriation’— firstly, Arroyo warns against the impulse to carelessly “wear headdresses or Native American beads and jewelry at music festivals” (Arroyo 10); secondly, Arroyo warns against “patching together traditions and beliefs from various Nations and even other world religions to suit an individual’s needs and fill a spiritual void” (Arroyo 11). This reminds me: I proceeded in the Order Of The Arrow until I attained the rank of ‘Brother’ in 2012, and I proceeded in the Boy Scouts until I attained the rank of ‘Eagle’ in 2014.

Profound People amidst Imperfect Institutions

[Sources: the left most picture is from ‘ESCONDIDO: Blue Star Bash benefits troops and their families’ (San Diego Tribune), originally published during September 26th, 2009 at 10:35 PM PDT; the other 2 pictures came from my photo libraries.]

Although I’m so thankful for my many positive experiences in the Boy Scouts™, I’m also somewhat disappointed in my experiences with the Order Of The Arrow™— since these mixed emotions would probably take another blog post to continue explaining, I’ll have to settle for sketching why I have mixed emotions here. While I would say that many people who I met through the Boy Scouts and the Order Of The Arrow are profound and fantastic, I want to be honest and acknowledge that these institutions are imperfect (cf: Sounds Like A Cult, February 7th, 2023).

For starters, I think that Arroyo would probably say that the Order Of The Arrow is guilty of impolitely ‘appropriating’ Native American fashion and spirituality— and I’d have to (sadly) agree with that evaluation. I agree with Aren Cambre—the Scouting Maverick—that (1) “BSA has endemic brownface cosplay”, that (2) “OA’s core ceremonies celebrate the racist legacy’s goal: a dystopia with fully debased tribes, with nobody to own tribal customs”, and that (3) the Order Of The Arrow is most definitely a “weird, racist, secret society” which “refuses to change”. Also, I agree with Ozheebeegay Ikwe’s assessment—within ‘The Last Real Indians’ piece entitled as ‘Boys Scouts Order of the Arrow Guilty of Cultural Appropriation’—that “While native children in residential schools had their culture and language beaten from them, the Boy Scouts were using the language and their version of ‘Indian culture’ in their OA ceremony.” If Arroyo were to look at the Guild of Inductions Experience Designers’ claim that it is possible to simultaneously quit misappropriating Native American culture while still lovingly retaining “Indian lore in the Order” (GIED), I suspect that Arroyo might say that loving Native Americans instead would look like if the OA were to cease from invoking Indian lore in the first place. Even though Ernest Thompson Seton (a founder of the ‘Woodcraft Indians’, influencing Boy Scouts’ founder Robert Baden-Powell) “was an animist adopting aspects of Native American spiritual beliefs”, and even though his “promoting ‘playing Indian’ by white children contributed to the reinforcing the stereotypes he opposed”, I think it is perhaps worth being thankful if indeed it was the case that “Seton attempted through lectures and writings to shift the feelings of hatred felt by nearly all white people towards indigenous people” (David L. Witt) Then again: even if we grant that “Some [non-OA camp fraternity] groups were so overtly racist that they stated it in their secret by-laws.” (OA Scouting), should we then turn a blind eye to covert racism (Culture Ally) which the OA still seems to exemplify? Upon reflection, I am joining Rev. John Norwood (a Lenni Lenape elder and Christian pastor) in declaring that “the use of Native dress and ceremonies (even when accurately portrayed) by non-Natives is a misappropriation of our [Lenni Lenape] culture” (Indian Country Today News). Even if it is easy to be ‘colonial’, are we therefore supposed to be content with “ignoring or downplaying colonial atrocities”? (Current Affairs) Even if it is easy to be apathetic or hateful to our neighbors in life, should we not seek to become as compassionate and loving as possible?

Additionally, I’d like to mention that I think the Order Of The Arrow institution could do better—for one other instance, for now—in recounting the history of the OA theme song. Although the official Order Of The Arrow website correctly says that the lyrics were written by Edward Urner Goodman (1891-1980) around 1921, the OA website omits some insightful history behind the melody— namely: the same melody was used for the Christian hymn ‘God The Omnipotent’ (1842; 1870); before then, in 1833, it was well-known as the Russian national anthem ‘God Save The Tsar’ (somewhat relatedly: consider Leo Tolstoy’s ‘Christianity and Patriotism’, which mentions ‘God Save The Tsar’). As a Christian, I love Christian people. As a human being, I deeply appreciate that Russian folks exist just as much as I deeply appreciate that United States of America folks exist. However, should I automatically approve of what Dorothee Soelle would call ‘Christofascism’? Should I not join her in thinking that “It is the historian’s job to determine how great a part Christian training in obedience played in laying the groundwork for [e.g. Nazi] fascism”? (Beyond Mere Obedience, Ch. 2, Pg. 19) Should I not join Soelle in feeling that we should “ask why the Christian-authoritarian understanding of obedience is so subjective, so mono-linear”? (Beyond Mere Obedience, Ch. 4, Pg. 32) And should I not join Soelle in bewaring of “[Christian] theologians who are so ideologically isolated that a happening like Auschwitz never moves them to alter their position”? (Beyond Mere Obedience, Appendix, Pg. 83) I do not think that Christianity equals Christofascism, and I will join Dorothee Soelle in bewaring of Christofascism— whether it pops up in Germany, in Russia, or in the United States of America.

(Concerning the dangers of Christofascism, consider the following: Stephen Waldron’s ‘What Was A Nazi Church Service Like?’; Clyde W. Barrow’s ‘The US Republican Party Will Continue Its Christo-Cascist Crusade’; John Whitsett’s ‘Authentic Christianity vs. Christian Nationalism’; Chris Hedges’ ‘Is the US Turning Into a Christofascist State?’; Andrea Watkins’ ‘Project 2025 is more than a playbook for Trumpism, it’s the Christian Nationalist manifesto’; Adam Joyce’s ‘The Church Isn’t Anti-Fascist…Yet’; Thomas Geoghegan’s ‘God or Trump’; Rev. Julie Calhoun-Bryant’s ‘What is Christian Nationalism and How does it Distort the Gospel of Jesus Christ?’; Dannis Matteson’s ‘Resisting Christofascism Today’, etc.)

At any rate: if the founding of the Order Of The Arrow™ institution has such imperfections (covert racism and Christofascism), then what about the founding of the Boy Scouts™ as an institution? Toward the beginning of Dr. Sam Pryke’s piece on ‘The Popularity of Nationalism in the Early British Boy Scout Movement’, Dr. Pryke alerts us about the scholarly works of Dr. Michael Rosenthal (he thinks Rosenthal is “relentlessly scornful”), Dr. Tim Jeal (he thinks Jeal is “more sober and thorough”), Dr. John Springhall (he thinks Springhall has published a “most impressive body of work”), and Dr. Allen Warren (he relates how Warren argued that Scouts were less militaristic than other Edwardian Britain youth organizations). Within ‘A Bad Scout?’, Dr. Rosenthal expressed his point of view that Scouting was militaristic in origin as it had been born out of “the trauma of the Boer war”— it was not Rosenthal’s intention to “undercut the value of scouting or to suggest that it didn’t develop in different ways over the next eighty years”. It seems that Geoffrey Wheatcroft thought that Dr. Jeal wrote an “excellent” biography about Baden-Powell’s eccentric nature (Slate, Aug. 27th, 1999), Brooke Allen thought that Dr. Jeal wrote a “superb and definitive” work detailing how Baden-Powell seems to have kept his homosexuality as secret as he possibly could have (The New York Times, July 9th, 2012; cf. KnowledgeNuts), and Jon Manchip White expressed the thought that “the more deeply [Jeal] probes his subject, the more Baden-Powell emerges as a sycophant, a toady and a ruthless egomaniac and careerist.” (Chicago Tribune, April 8th, 1990) Although I am sorry Baden-Powell was made to feel like he had to repress his homosexual orientation, and although I would perhaps welcome his eccentricity, I would push back against any exploitative impulses which Baden-Powell might have exemplified.

Like Dr. Rosenthal, Dr. John Springhall has argued—within his piece on ‘Baden-Powell and the Scout Movement before 1920: Citizen Training or Soldiers of the Future?’—that “The Scouting movement before I9I4 should, therefore, be seen within the 'context' of preparing the next generation of British soldiers, volunteers and conscripts to be more efficient, characterful and self-reliant than their Boer War predecessors, however much official Scouting rhetoric may have claimed 'good citizenship' as its overriding aim.” (Springhall 942) This warmongering undertone gives me pause. Further, this has been said: “MI5 files declassified in 2010 show that Baden-Powell was invited to meet Hitler after holding discussions about building closer ties with the Hitler Youth programme” (The Guardian). Even though it has been said that Baden-Powell did not meet up with Hitler and that Hitler’s Youth became hostile to Scouts (World Scouting), I am just now becoming conscious of the perspective that “the founder of Scouting was an imperialist, a monarchist, a brute, a war criminal, a shameless racist concerned about ‘the moral tone of our race,’ and an anti-Semite who openly expressed admiration for Mussolini and Hitler and praised them for having ‘done wonders in resuscitating their people to stand as nations’” (Jewish Press; cf. Jennie Rothenberg Gritz’ January 30th 2013 piece for The Atlantic). In response to Corrie Drew’s allegations against Baden-Powell (see BBC’s ‘Robert Baden-Powell statue to be removed in Poole’ and ‘Was Robert Baden-Powell a supporter of Hitler?’, which were part of many conversations bound up with Stop Trump Org’s ‘Topple The Racists’ movement), Colin Walker—who runs the Scout Guide Historical Society website—has suggested that Baden-Powell “changed his mind and in 1935 publicly criticised both Hitler and Mussolini” (Gyronny Herald). I do not know the degree to which Baden-Powell may have been (unfortunately) fascistic, but I think I agree with the following sentiment— once upon a time, a Steve Martin had written to the Editor of the Los Angeles Times and professed thusly: “Baden-Powell, along with Winston Churchill and Theodore Roosevelt, were racist imperialists. But we can honor their positive contributions while acknowledging their faults.”

Returning to Arroyo’s book, I think it is worthwhile to observe the following:

“The relationship between Native Americans and the United States government remains fraught. Centuries of attempted genocide, violence, and forced assimilation have had a profound impact on Native American people and their various practices. Depending on where they lived, they may have been forced to leave their ancestral lands, were obligated to convert to Christianity, had some of their most important Ceremonies banned, or were murdered by the thousands. To this day, there have been no meaningful reparations on behalf of the United States government, and it was only in 2022 that the Canadian government agreed to a mass financial settlement with their First Nations.” (Arroyo 23)

A Couple Lingering Questions:

What could ‘meaningful reparations’ look like?

Having been educating myself about the history of the Order Of The Arrow™ as well as of the Boy Scouts™, how can I better educate myself on Muscogee Creek Nation history— insofar as I have Muscogee blood running through my veins?

Stay tuned for the next post in this series, wherein I aim to continue sharing nuggets of wisdom from local public library books!

P.S. Thank you for being you and thank you for reading! ♾️ 😎 🖖🏻 🙏🏻 ♾️

P.P.S. I’d love to connect— here is my LinkTree!